As a product of the 50’s, I grew up in a household where the mother nurtured her offspring and the father brought home the bacon. If I wanted to talk about friends, clothes or boys, I went to Mom. If I wanted to negotiate curfews, chores or my allowance I went to…also Mom. Then, of course, she would run whatever it was by Dad. Mom was more than just the nurturer in our family. She was the mediator as well.

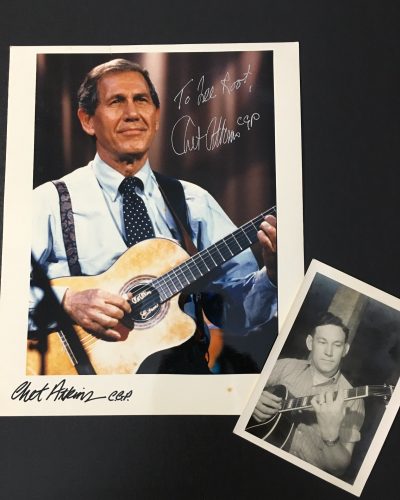

Although I don’t think it was intentional, my dad could come off as pretty darned intimidating. A rather stoic man, he seemed encased by some invisible shell that made him untouchable. That was my perception, anyway. As a young girl, I had no clue how he felt about me. Oh, I suppose that’s not entirely true. He must have considered me an okay kid because he never beat me, locked me in a closet or made me pay rent. But we certainly didn’t have what you’d call sit-down conversations. We didn’t even chat. The main interactions I can recall from childhood were the times I timidly lurked in Dad’s workshop while he worked on some project and listened to Chet Atkins. (When it came to Chet, Dad was a bit of a fanboy.)

I’d stay out of the way, anticipating what I hoped would come, and it usually did. Dad would put down his tools, grab his guitar and start picking along with Chet. The fact that I was there never seemed to bother him, and I loved those little encounters. I doubt my dad had any idea how tickled I was during those moments but, each time, I felt as if he and I shared some unspoken, albeit brief, connection.

More often than not, though, I observed Dad from afar…and with a touch of trepidation. To put it simply, I never mistook my dad for Ward Cleaver.

The first indication I didn’t know him as well as I thought I did was when I was a young wife and mother. My husband was in the service, and we were moving from Indiana to Rhode Island. Right before we left, Mom and I embraced in the driveway and vowed to call and write as often as we could. I then gave Dad a perfunctory hug before I got in the car. I imagine we mumbled something to each other, but I really can’t be sure. I settled into the passenger seat and, just as we started to back out of the drive, Dad took out his big white handkerchief and wiped off the headlights. I began to sob. My husband didn’t have a clue what caused the waterworks, but that gesture of Dad’s was as plain to me as a billboard on a highway. It was his way of saying he loved me and wanted me to be safe. Nearly a half-century has passed since that moment, yet I can see it – and feel it – as distinctly as if it were yesterday.

That little chink in Dad’s armor cast him in an entirely different light. As the years passed, I finally found my voice with him and made the most fascinating discovery. He truly was quite a guy. I always knew he was intelligent, methodical and sometimes demanding. But I found out he was also funny, compassionate and a joy to be around. We’d talk and laugh and, quite often, just sit together in comfortable silence. I grew to appreciate all the attributes that caused my mother to fall in love with him a lifetime before.

When health problems rendered Mom disabled, Dad suddenly had to take over all of the domestic responsibilities. That worried me because the household had been her bailiwick, not his. He was in his seventies, having to learn it all, and I was afraid he’d be overwhelmed. But not only did he manage to cook, clean, and pay the bills on time…he did so with apparent ease. Mom even joked about what a great chef he was. She swore he gave Emeril – a big deal on TV at the time – a run for his money.

The true test came when my mom was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. Dad was determined not to let her live out her final days in a nursing facility, and he took Mom home to die. Home to the cabin he had built for her, nestled among the poplar trees she loved. Hospice aides and family members pitched in to assist, but Dad was Mom’s primary care giver. He was meticulous in his new role, and he wanted only the best for her. He painstakingly doled out her medications, bathed her, diapered her, kept her company and simply loved her. In so doing, he revealed a side to his character that I’m not sure even he knew existed.

Dad and I grew closer during the year leading up to my mom’s death. I lived in another city but went to the cabin as often as I could to help him and my brother tend to Mom’s needs. Though often weary and sometimes depressed, my dad didn’t complain. Even so, the physical and emotional toll it took on him was a constant concern for me. I feared that after Mom was gone, I’d lose him, too.

Shortly before my mom’s death, Dad started talking about some small trips he planned to take. It was the first time he’d even mentioned life after Mom, and it was such a relief to know he wasn’t just going to give up and stop living.

When the time came, Dad took over Mom’s final role…that of the family nurturer. It didn’t particularly come naturally for him, and he never got in the habit of randomly calling to chat the way my mom did, but he was there to listen if needed and he always enjoyed getting together with family. He even found Mom’s old address book – which was complete with dates for anniversaries and birthdays – and continued her practice of sending cards to commemorate those events.

Back then, losing Mom was the hardest thing I’d ever experienced. Finding Dad was one of the best. When he died over a decade later, the loss I felt was just as deep as it was when I had to say goodbye to my mom. I was fortunate to have been encompassed by her love for 45 years, but I felt I’d had Dad for such a short time in comparison. It wasn’t nearly long enough to make up for all the early years when I didn’t see him for who he really was.

As fleeting as those last years with Dad were, we made good use of that time for as long as we could. To me, Lee Root was an amazing man and, in the end, he wasn’t just my father. He was my friend.